Every time we enjoy our favorite meals, an invisible enemy is hard at work on our teeth. Dental plaque, that sticky film, poses a major risk to our oral health, yet many of us know little about it.

Understanding the nuances between seemingly similar terms like plaque and tartar can be vital for maintaining a healthy smile. Dentists have various methods for identifying the buildup of plaque, a crucial step in preserving your dental well-being.

The distinction between plaque and tartar

Dental plaque and tartar are closely linked in terms of oral health but differ significantly in their characteristics and management. Plaque is a sticky film that forms on the teeth when oral bacteria feed on sugars from food and drinks. This soft, fuzzy substance can usually be felt on the tooth surface and develops rapidly within a day. With proper oral hygiene practices, such as regular brushing and flossing, plaque can generally be managed and removed.

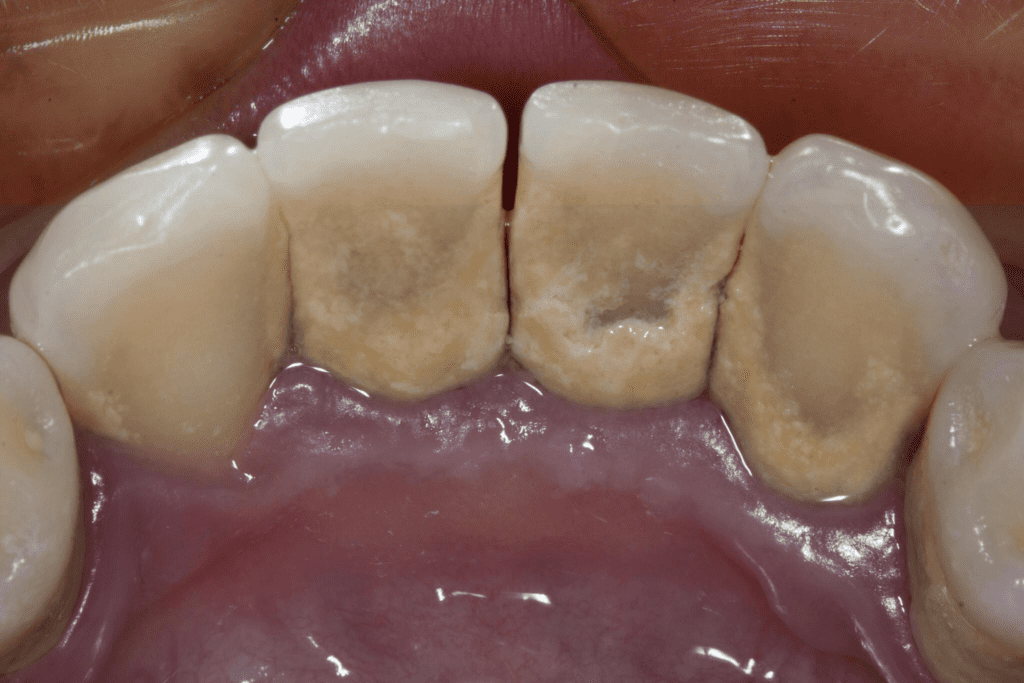

In contrast, tartar, or dental calculus, presents a greater challenge. Tartar is essentially plaque that has been left unchecked and has hardened over time due to the absorption of minerals from saliva. Unlike plaque, tartar forms a tough, shell-like layer on the teeth, and its removal is beyond the scope of routine brushing and flossing. Recognizably yellowish or brown, tartar buildup requires professional cleaning by a dental hygienist or dentist to prevent potential gum disease or tooth decay.

Here’s a brief comparison:

| Feature | Plaque | Tartar |

|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Sticky, soft film | Hard, shell-like layer |

| Formation Time | Forms within 24 hours | Gradual buildup |

| Removal | Brushing and flossing | Dental professional |

| Prevention Tips | Proper oral hygiene | Regular dental visits |

Maintaining a routine of effective oral care, including the use of fluoride toothpaste and perhaps an electric toothbrush with soft bristles, can help prevent both plaque and tartar from threatening your dental health.

What is the diagnostic process for plaque?

Dental plaque is a sticky film of bacteria that constantly forms on our teeth. It’s often colorless or pale yellow, making it tricky to detect without a professional eye. During a dental checkup, your dentist or dental hygienist may use a small mirror to inspect your teeth for signs of plaque buildup. To aid in the diagnosis, oral health experts might apply a special plaque-disclosing agent—this substance contains a dye that turns bright red when it comes into contact with plaque, highlighting areas of concern.

For those keen on self-assessment, there are over-the-counter disclosing gels or tablets. When used as directed, these products stain plaque, making it more visible. However, it’s important to know what to look for as plaque may not always be obvious to the untrained eye.

The degree of plaque accumulation and its potential hazards can differ from person to person. If left undisturbed, it can harden into tartar, contribute to gum disease, and lead to tooth decay. Regular dental cleanings and good oral hygiene practices, such as brushing with fluoride toothpaste and using an electric or soft-bristled toothbrush, are crucial in managing plaque.

| Signs of Plaque Buildup |

|---|

| – Persistently bad breath |

| – Red, swollen gums |

| – Bleeding gums |

| – A fuzzy feeling on teeth |

Incorporating these oral hygiene routines can help maintain healthy teeth and prevent the onset of periodontal disease.

Components of plaque

Dental plaque is a translucent, sticky coating that continuously forms on the teeth. This dental biofilm is primarily composed of bacteria that feed on the breakdown of sugars, particularly sucrose, provided by our intake of sugary and starchy foods like candy and potato chips. These microorganisms are anaerobic, gram-negative bacteria, known for thriving within the oxygen-free environment that plaque offers.

Commonly accumulating around the gum line and in the narrow spaces between teeth, plaque is a breeding ground for bacteria. It can take hold mere hours after one has finished brushing, heightening the necessity for consistent oral hygiene. While regular brushing can generally remove plaque, neglecting to do so leads to its calcification into tartar—a substance only removable via professional dental cleaning.

Riddled with a complex array of microbes, dental plaque is the chief contributor to oral afflictions such as tooth decay and periodontal diseases, which can escalate into serious health concerns if left unchecked. Proactive oral care practices, including the use of electric toothbrushes and fluoride toothpaste, can help manage the persistent challenge plaque presents to maintaining a clean and healthy mouth.

Bacteria

Dental plaque teems with a multitude of bacterial species, creating a robust biofilm on the surface of teeth. These oral bacteria feast upon food particles left behind after eating, particularly sugars, starches, and refined carbohydrates. During this process, the bacteria produce acids that can erode tooth enamel, potentially leading to cavities and tooth decay.

The bacterial toxins produced in plaque can provoke inflammation, redness, and swelling in the gums—a condition that may escalate into gum disease or periodontitis. The spread of these bacteria through the bloodstream can link oral health to broader systemic health issues, reinforcing the importance of dental hygiene in overall wellness. With a strong bias towards acidogenic and acid-tolerating microorganisms, the bacterial landscape within plaque is significantly influenced by dietary habits and fluoride exposure, critical factors in the development of dental caries.

Early colonisers

In the intricate ecosystem of dental plaque, the early colonisers hold the fort. These pioneering microorganisms, which include Streptococcus species, Eikenella spp., Haemophilus spp., Prevotella spp., and Propionibacterium spp., are adept at adhering to the tooth surface and laying the groundwork for the eventual plaque formation. In particular, Streptococcus species are prominent, comprising between 60% to 90% of this initial microbial population.

By establishing the initial biofilm matrix, these early colonisers create a welcoming environment that facilitates the attachment and proliferation of subsequent bacteria. The diversity of these early settlers is pivotal, fostering a varied and dynamic community that underpins the dental plaque biofilm.

Supragingival biofilm

Supragingival biofilm is the plaque that resides above the gum line and is visible upon close inspection. As the most accessible form of plaque for removal through brushing and flossing, its presence is significantly influenced by one’s oral hygiene routine. Following tooth brushing, it swiftly re-forms, populating areas such as interdental spaces, pits, fissures of the teeth, and along the gingival margin.

This type of biofilm is chiefly made up of aerobic bacteria, which depend on oxygen for survival. Nevertheless, if plaque persists over time, anaerobic bacteria begin to flourish, further complicating the plaque’s composition. Salivary proteins such as alpha-amylase, proline-rich proteins, and statherins play a critical role in the genesis of the supragingival biofilm, underscoring the complexity of interactions between oral bacteria and the host.

Subgingival biofilm

Beneath the gum line, a different kind of plaque develops, known as subgingival biofilm. This variety of biofilm is composed of microorganisms that are adapted to the unique environment provided by the subgingival space, an area less exposed to oxygen and home to a more diverse community of bacteria.

The presence of subgingival plaque is of particular concern since its accumulation is a driving force behind periodontitis, an advanced form of gum disease. The inflammation and damage associated with subgingival biofilm impact not only the gums but also the integrity of the bone supporting the teeth. Detecting and managing subgingival biofilm is pivotal for oral health preservation, underlining the necessity for regular dental checkups and interventions such as professional cleanings.

How to treat plaque?

The treatment for dental plaque involves maintaining a rigorous oral hygiene routine to prevent its accumulation. Key strategies include:

- Brushing Regularly: Brushing your teeth at least twice a day with a soft-bristled toothbrush is essential to dislodge food particles and bacteria in plaque. An electric toothbrush can add efficiency to this process with its oscillating bristles.

- Flossing Daily: Using dental floss reaches areas your toothbrush can’t, such as between the teeth and under the gum line, helping to prevent the formation of gum disease.

- Toothpaste Choice: Fluoride toothpaste strengthens tooth enamel against decay, and those containing baking soda can be especially effective in breaking down the sticky film of plaque.

- Professional Cleanings: For hardened plaque, known as tartar or calculus, visit a dental professional for regular cleanings. A dental hygienist uses specialized tools to remove tartar buildup, significantly reducing the risk of periodontal disease.

- Healthy Diet: Limit sugary and starchy foods like potato chips that contribute to plaque formation. Focusing on healthy teeth through diet is a proactive step in oral health care.

By conscientiously caring for your teeth with these methods, you can keep plaque at bay and enjoy a healthier smile.